I just started doing some freelancing again, pitching story by story. Who I am working with will be revealed in due course once the first new story is published. (Promise! I’ll post it here).

As I wait for phone calls from potential people to interview, I am thinking back to my chase producing experiences at the CBC. I always try to go back to the methods I developed while I was there to keep my productivity up as a freelancer. It was a time when the expectations were high, and the pace somewhat crazy. The things I learned at CBC have helped me support my growth as a journalist. Here’s what I did and what I learned in that intense time.

The example I am using here is from the time when I was chase producing for a regional current affairs program, similar to the local shows you’d hear from your local CBC stations in the morning, at noon or the 4-6 slot. Those shows are a mix of interviews, music, news and weather reports. Most of the interviews were 6-7 minutes long and we usually had 4 interviews in the course of an hour.

Here is the way my day would unfold:

8:30 – story meeting with the producer, the program host and the researchers and associate producers – 5 new story pitches were expected each day from each of us. So I constantly had to be on the lookout for good stories. Usually two or three of those five were chosen as topics to ‘chase’ (hence the term ‘chase producer’). They wouldn’t all have to be for the next day’s show — the producer would designate which ones he wanted for which days. Sometimes they were for the next day. And, if there is a very time sensitive story, it might even have to go in today’s show two hours later. And, sometimes the stories just didn’t pan out. C’est la vie. If I stick to this plan, my success record was pretty good.

9:00 – 3:00 The chase begins. My time was mostly spent doing research to determine the most suitable guests, including phone numbers. Potential guests would be phoned to check out their suitability and availability to appear on the show. Lots of waiting around for phone calls to be returned. If the potential guests didn’t call back, I’d call the next suitable person on the list.

In between waiting for phone calls, I developed story ideas and did research for new ideas to be presented at the next day’s story meeting. The show was mostly comprised of single interviews, so I was generally looking for one guest per story.

So I phoned. And emailed. And phoned and emailed. Rinse and repeat. Some days were easier than others. Vacation time, like March break and Christmas, made it harder to book guests. If it looked like a story I’d been assigned wasn’t going to come in for the next day’s show, I talked to my producer to let him know we needed to change course. If a story wasn’t coming together by 3:00, I usually quit chasing it and focused on something that looked more likely.

Generally, it was expected that at least one story I was working on for the next day would pan out. Many days I had two stories ready to go (which, if we already had enough for the next day’s show, the extra one could usually be scheduled for the day-after-tomorrow show). If the stories were fairly easy, I could do three a day. But that didn’t happen too often. On days when I was working on subjects that were more complex, I only did one.

The bottom line was — an occasional day when a producer didn’t have a story for the next day was generally acceptable. But it better not happen too often. That’s why was always a good idea to have extra stories my back pocket almost ready to go. (I remember one memorable days when somebody else’s guest bailed fifteen minutes to air time. The producer dropped a 15 minute interview on my desk on a reel of tape and told me to find a good 5 minutes and have it ready in 20 minutes to go to air. I did it. I’m proud of that.)

3:00 – With my guests confirmed for the next day, the last part of the day was spent preparing background notes, scripts and questions for the host. Do you ever wonder how a program host is able to know so much about so many things and sound so relaxed with all the people they’re interviewing? Most of the time, the research staff has prepared the materials for them. The host uses the materials prepared by the production crew as the roadmap for the interview. The background notes gives the host the larger context so they can make the interview their own. If, for example, the host gets caught in traffic and show up late, they’ll still sound totally in control of the materials as though they did the whole story themselves.

5:00 And then I went home, still looking for story ideas all the way home. And the next day it started all over again.

And now, in my freelance practice, I try to keep the same flow. The key is to be working on several things at once. Keeping new ideas flowing, trying to stick to deadlines, but understanding that things don’t always pan out. But, always having another story in the wings so everything doesn’t come to a grinding halt.

This was from a time before there was social media. My rhythms are slightly different now but basically the same. The secret to success is having more ideas than I can use in various stages of readiness. And that way, I stay on top of things without panicking about the prospect of dead air.

Big thanks to Kate Romain for our new House of Sound and Story logo!

Big thanks to Kate Romain for our new House of Sound and Story logo!

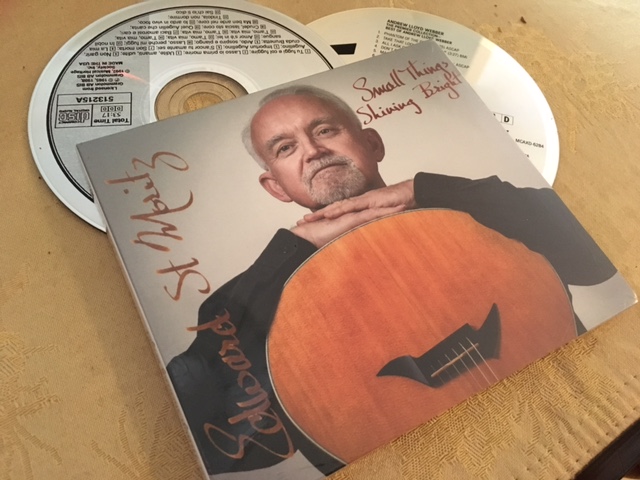

Okay – I’ll bet you’re wondering. If we’re talking about microphones, why do I have a picture of a bunch of dudes playing soccer under a floodlight?

Okay – I’ll bet you’re wondering. If we’re talking about microphones, why do I have a picture of a bunch of dudes playing soccer under a floodlight?